Decentering Whiteness

Decentering Whiteness narrates stories of Black persistence and resistance against white supremacy and violence in the United States. Shifting the focus and power from whiteness is the first step in dismantling racial oppression and violence. This shift allows us to pay close attention to how Black people resisted and persisted through extreme conditions.

Although slavery legally “ended” in 1865, Black people were, and in many instances continue to be, excluded from all areas of economic and political life. They/We are consistently asked to “prove” their/our worth and loyalty to “American” ideals under duress. This exhibit explores how historical and contemporary experiences of violence, systematic disenfranchisement, and suppression of rights have required continued resistance and persistence in the fight for justice and equity.

Playlist for Decentering Whiteness

Setting the Stage: Refugee Resettlement

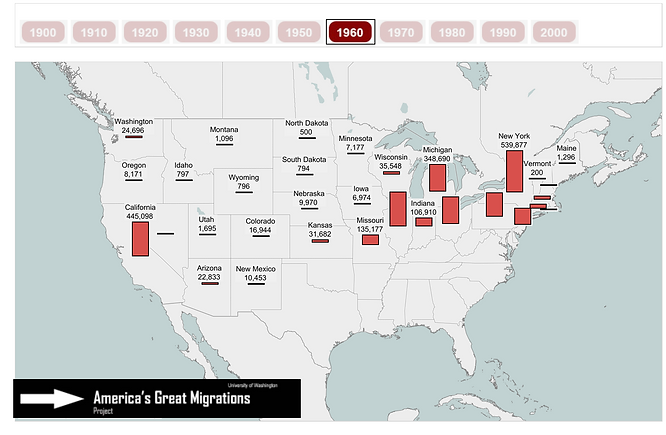

These interactive maps, created by James Gregory from the Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, reveal many phases of migration. You can select a specific decade, hover over a state to see how many people moved there, or select a birth state to see trends in migration.

Click the image to visit America's Great Migrations

From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, over 7-12 million Black Americans fled the south and resettled in cities across the north. This number is inexact because many had to leave the south in secrecy to avoid being killed, and racist practices in the south meant that Black people were undercounted. There is no accurate number of Black people who lived in the south.

As they sought refuge in the north, Black Americans not only reshaped the development of major American cities and small towns, they irreversibly changed the texture of American music, professional sport, literature, science, and economic contributions. Some of their contributions have, at best, been forgotten, and at worst, been violently erased.

Proving Your Americanness: Historical and Contemporary Voter Suppression

State of Louisiana Literacy Test

This test was given during the late 1950s to anyone who was not able to prove that they had a fifth-grade education.

Voter tests were required as a tactic for voter suppression. Each person was given 10 minutes to complete this 30 question test. One wrong answer resulted in the inability to vote. Can you pass this test in 10 minutes?

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Milwaukee normally has 180 voting sites; fewer than 12 polling places will be open April 7

Current-Day Voter Suppression

US mailboxes being removed so absentee ballots are harder to send in

The Economic Impact of Resistance and Persistence

The emergence of Black affluent areas, often named “Black Wallstreet,” consistently resulted in riots, massacres, and other acts of violence enacted by White mobs and the police. These areas that once produced hundreds of millions of dollars in Black wealth were destroyed and continue to be blighted areas today.

Smoke billowing over Tulsa, Oklahoma during 1921 race riots

Alvin C. Krupnick Co.

1921

Photograph

Credit: Library of Congress

From May 31 through June 1, 1921, in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, White rioters destroyed more than $200 million of Black property in today’s dollars. This is known as the Tulsa Race Riot or the Tulsa Race Massacre.

White mobs stole money and valuables from Black households. They destroyed more than 1,200 homes and looted another 314. Some Black families became refugees, living in Red Cross tents, while police and the National Guard imprisoned other Black residents. Others fled Tulsa. White looters had eradicated Black wealth in Greenwood within a matter of hours.

Courts decided the city of Tulsa was not financially liable for the mobs’ actions. Insurance companies avoided claims by citing clauses that released them from damage payouts due to riots. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court chose not to hear a case seeking reparations for survivors and descendants after lower courts ruled the statute of limitations had expired.

The failure to provide reparations does not simply affect the direct victims of collective white violence. In the context of Tulsa, reparations refer to payments from insurance companies for loss of property and loans from banks to rebuild. This is part of a larger system that denied household assets for later generations of African Americans. The withholding of reparations conveyed a message that White violence would be condoned and tolerated.

“From a 10-room and basement modern brick home, I am now living in what was my coal barn. . . From a five-chair white enamel barbershop, four baths, electric clippers, electric fan, two lavatories and shampoo stands, four workmen, double marble shine stand, a porter and income of over $500 or $600 per month [Approximately $8500 per month today], to a razor, strop and folding chair on the sidewalk.”

- Testimonial of C.L. Netherland

Perils of Persistence and Resistance

Content Warning: The following section includes visuals of lynchings

From lynchings to police brutality; this section captures the perils of resisting and persisting for justice.